With No Right To Warm Welcome: Life, Survival In Caracas Slum

Umer Jamshaid Published March 21, 2019 | 09:37 PM

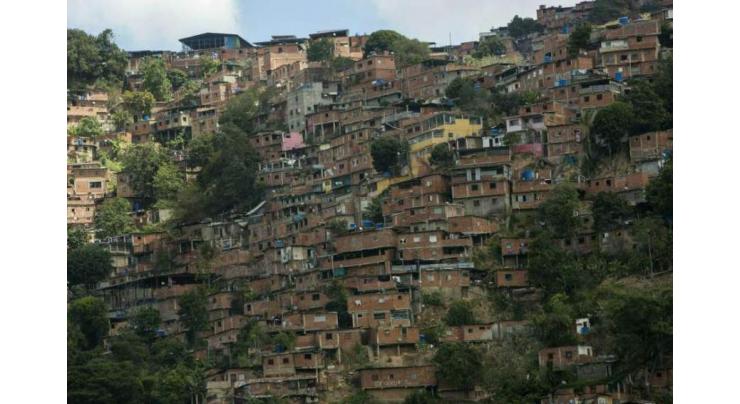

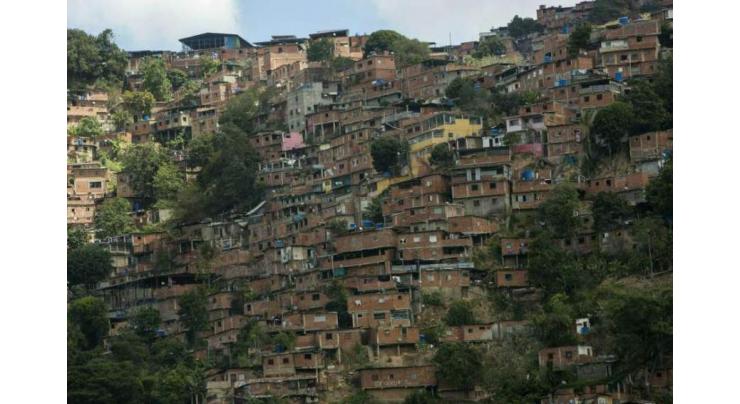

High walls, barred windows and armed guards have become a common sight for the residents of Petare, the largest and most dangerous slum area in Latin America, which is located in eastern Caracas

So many crimes are committed here every day, that the Venezuelan government has already stopped keeping track of them. However, despite the infamous reputation of this place, which is skipped by all other residents of Caracas, the life here is very active the life that is hidden from the rest of the world, but is full of emotions, colors and human tragedies.

A Sputnik correspondent visited Petare and found out what dangers one can face in the slum of the Venezuelan capital, which is unsafe even for the police.

A taxi driver stopped the car near a metro station, the last bastion of civilization, behind which the "foreign ground" begins, and told me in an uncompromising manner that he would not go any further and it was time to pay. I paid for the trip and got out of the car, immediately picking up tens of different smells: sewage, dust, rotten vegetables and fruit, roasted meat, human bodies. Caracas impresses everyone, who comes to the city for the first time, with its indomitable energy.

The spirit of the Latin American's past was intertwined there with the rhythm of a modern metropolis, whose citizens call it "the second New York." In the daytime, the streets are always full of people, especially in rough areas, and the fuss does not stop for a moment. People rush around with their work, women take their kids to school, and local salesmen spend hours in heated debates about politics.

Most of the residents of Caracas were burdened with their daily worries, and the sudden appearance of a lonely "gringo" (foreigner) in this zone, which is closed for foreigners, did not create hype. After walking about 30 feet, I found myself in a small cafe. In a short time, other visitors, who were watching me closely at first, lose all interest in me, making me think that my integration into the local environment was successful. I ordered a coffee and waited for a guide.

Soon, two people on motorcycles drove up to the cafe. One of them entered the cafe, looked around and, after noticing me, said "Let's go."

We were moving past slum houses at a rapid speed, getting through the streets within seconds. Motorcyclists were driving carelessly, from time to time crossing into the line for oncoming traffic. It was obvious that they felt at home. But a few minutes after the journey began, I felt disoriented and did not know, to which part of Petare I was being taken.

No one knows exactly how many people live in Petare. According to the authorities, today, the population of this area is more than a million people. The city is divided into numerous quarters, there are at least 2,000 of them. Each quarter has at least two gangs operating there. The relationship between them varies from fragile neutrality to blood feud. However, according to a high-ranking officer from the Sucre Municipality, there have been a truce between the most of gangs in recent months, which made the lives of ordinary citizens relatively calm.

The Venezuelan capital is divided into the city and the barrios, quarters similar to Brazilian favelas that consist of dilapidated houses tightly adjoining each other. The streets with all these houses circle along the sides of the hills, which wrap around Caracas, and stream through the city. There is no sewage system or electricity in the area, and the roads more look like mountain trails which makes motorcycles the main means of transportation. There are no clear borders, which would separate nicer areas from the barrios, and they often coexist with each other.

For example, the central El Silencio quarter is located next to one of the largest barrios of Caracas, San Agustin. Their sizes range from small areas to mini-cities, such as Petare, which have their own shadow economy, zones of influence, verticals of authority, and even tourist services.

An ordinary driver will not take one there, as he does not know these places and it is highly possible that he has never been there. One has to make arrangements with guides, who usually come from barrios themselves and can provide people with a safe corridor. They take a lot of money $300-500 on average and warn that strangers here are treated with great suspicion, and one should not expect a warm reception. However, there are simply no other options to get to the area without getting into trouble. The crime situation in such areas is so difficult that even police officers prefer not to appear there, except for conducting major special operations.

After reaching our destination, I and my guide found ourselves in front of an ordinary three-story house. Two large Latin American men with assault rifles in their hands stood in the doorway. After a few minutes of waiting, the men let us into the house. While stepping into the house, I turned my head and finally noticed that the windows of that and other nearby buildings were barred from the first to the last floor.

After a thorough search, we were led into a dimly lit room with scruffy walls. The decor was modest: a wooden table, an old rag sofa and a small bookshelf with a faded photo of an elderly man. The paint on the walls was cracked and peeling. Several people, including a former leader of a large paramilitary group in Petare, 43, were already waiting in the room.

There was one more search, after which the time of the interview came. I was allowed to take only a pen and a notebook.

The first question was about the economic crisis in the country.

"The situation in the economy hit us all. But in general, thanks to the crisis of recent years the crime in Venezuela has significantly decreased. Few citizens carry Dollars with them, and the national Currency has depreciated so much that robberies, including bank robberies, have become deliberately meaningless. Patrons and weapons have also become too expensive, as well as spare parts for motorcycles. Therefore, in some way, the crisis is not a bad thing for ordinary citizens," the man said.

He also stressed that it was no longer reasonable for the criminals to take the risk of robberies.

A man with a harelip, who was sitting next to my first speaker, noted, however, that not all kinds of crime were decreasing. For example, smuggling was flourishing. As the state was subsidizing gasoline prices, local gangs were selling it at the border with neighboring Colombia for "huge amount of money." In addition, due to the recent energy collapse in Venezuela, the number of cases of looting have significantly increased, he added. Luxury goods were no longer the priority for robbers, as they were emptying counters and refrigerators in search for food.

Then I noticed a teenager, who was standing on guard at the door. It looked like he was no older than 15 or 16. I thought of how gangs recruited minors and what motivated the boys to enter the criminal world. The leader of the group said that all the stories were quite similar. Some of the teens were abandoned by their parents, some ran away from home because of abusive treatment, while others lost their families. Need and poverty turned out to be two main factors that pushed young people toward crime.

"Murder, kidnapping, drug trafficking all of this has become a part of routine life for Venezuela in the past few decades. Young people used to join groups because they saw that as an easy way to earn money and the ability to quickly receive status items: a mobile phone, a tv or a motorcycle. Now they are being recruited for food," the former leader stated.

He admitted that he, himself, began his career as a gangster rather early, at the age of 12. He is one of those few people, who managed to stay alive during his 25-year "career" in gangs. The man said he considered himself exceptionally fortunate.

"Only two of my acquaintances and friends, with whom we started working on the streets, are still alive, and they are serving sentences in prison. Very few people are able to afford the luxury of being in the drug business and stay alive until at least 35," the man assured.

Subsequently, with no peculiar nostalgia, he told about his childhood and his parents, whose life in Petare was a continuous attempt to make ends meet; about his farther, who worked at different building sites; about his mother, who worked as a servant for a rich family. He also told how his family was collecting potato skins so that his mother could cook some kind of soup for them; how they mixed milk and everything that could be mixed with water; how they had no money at all and he along with his younger brother had to steal in shops, where they were often caught and beaten by guards; how he made a promise to himself that neither he nor his relatives would ever be hungry again.

Speaking to me, the man remembered his criminal past as it was a bad dream. The hardest thing, he said, was providing for his own family.

"I could not let my wife and child come into contact with this world in any way. Of course, when I had an opportunity, I moved them to a safer area in another part of Caracas. For several years we lived away from each other, my son grew up without me. When he grew older, I had to explain my absence and say that I am a gold digger at the mine in the state of Bolivar," the man said.

He added that he did that all to protect his family.

"Many of us create a fairy-tale world for our loved ones to protect them from the bitter truth," he noted, summing up the conversation.

After the interview, we went up to the last floor and then on to the roof with a view of the evening Petare. Many houses there were painted with portraits of Venezuela's former President Hugo Chavez, as a token of appreciation and a sign of love of the people to their former ruler and the last legend of Latin America.

Related Topics

Recent Stories

Aiman Khan granted UAE Golden Visa

PSX achieves significant milestone, surpasses 72,000 mark

Pak Vs NZ T20I: Orphaned children extended special invitation to watch match

Finance Minister lauds UNDP’s unwavering support during floods

President Raisi leaves for Iran from Karachi

Currency Rate In Pakistan - Dollar, Euro, Pound, Riyal Rates On 24 April 2024

Today Gold Rate in Pakistan 24 April 2024

Punjab CM inaugurates Pakistan’s first Virtual Women Police Station

Dutch model Donny Roelvink embraces Islam

Experts raise concerns over introduction of 10-stick packs

Iranian president arrives in Karachi

Law Minister expresses Govt's resolve to address issue of missing persons

More Stories From World

-

Escaped army horses bolt through central London

49 minutes ago -

China to send fresh crew to Tiangong space station

49 minutes ago -

Critics fear Togo reforms leave little room for change in election

59 minutes ago -

Victims of China floods race to salvage property

59 minutes ago -

Blinken back in China seeking pressure but also stability

1 hour ago -

'So hot you can't breathe': Extreme heat hits the Philippines

1 hour ago

-

In Tajikistan, climate migrants flee threat of fatal landslides

1 hour ago -

Football: Italian Cup result

1 hour ago -

Biden pledges swift weapons delivery to Ukraine

1 hour ago -

China announces new partners for International Lunar Research Station

2 hours ago -

Astronauts of China's Shenzhou-18 mission meet press

2 hours ago -

Partial power outage at Fukushima plant, water release suspended

2 hours ago