Peshawar’s Wax Art Fading As Patronage Declines In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Mohammad Ali (@ChaudhryMAli88) Published July 22, 2025 | 03:10 PM

PESHAWAR, (UrduPoint / Pakistan Point News - 22nd Jul, 2025) In a modest home in Peshawar, nestled among dusty alleys that once echoed with the vibrance of artisans and storytellers, 74-year-old Riaz Ali sits surrounded by memories and masterpieces.

For over six decades, he has practiced the delicate art of wax painting, a craft passed down through three generations of his family.

But today, the flickering flame of this once-thriving tradition is in danger of going out due to neglect and lack of patronage in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

“I remember watching my grandfather create wax art before partition and later came to Peshawar,” Riaz recalled, his fingers gently tracing the faded edge of a 600-year-old peacock design hanging by his window.

“In those days, they used sifted mud and silver foil. Now, we use natural colours they are softer on the eyes and more elegant, attracting people.”

The tourists while staying at historic Qissa Khwani visited wax shops and took these products for loved ones as gift.

Riaz, who belongs to a family of artisans rooted in what was once known as Roghan art during the Mughal era, learned the skill from his father after the family migrated to Peshawar.

Over the decades, he painted everything from scarves and shirts to handkerchiefs and framed art. Each piece takes two days to complete and, once sun-dried, can last for years even surviving a wash without losing colour.

"I love wax painting due to its eye catching designs" said Ejaz Khan, a resident of Wapda Town Peshawar.

Ejaz Khan has purchased four wax paintings for its newly constructed house and two more as gift for his brother.

Riaz said that numbers of buyers of wax paintings has decreased in recent years due to lack of KP Govt patronage.

He said despite the enduring beauty and cultural legacy of the craft, wax painting has been slowly fading from public memory in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, urging Govt to provide interest free loans to its artists.

Riaz’s contributions to the preservation of wax art have not gone unnoticed. A recipient of the President’s Medal of Excellence in 2012, he was also awarded the UNESCO-CCI Seal of Excellence in 2004 for his unique work, selected from entries submitted by artisans across 11 South Asian countries.

His art has traveled to exhibitions in Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Nepal, and India, showcasing a heritage deeply tied to South Asia’s cultural fabric.

But despite international acclaim, Riaz has struggled to find local patronage. In the early 2000s, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government launched the Artisan Village project within Peshawar’s historic Gor Khatri Complex, a promising attempt to preserve the city’s endangered crafts.

Riaz served as a master trainer there, mentoring two students. One dropped out after marriage, and the other found employment elsewhere. The program's second phase never received funding, and with that, a vital opportunity for skill transfer disappeared.

“The government started something good, but it was never finished,” he said. “We need consistent support, not abandoned projects.”

Once a fixture in Peshawar’s Saddar area, Riaz’s workshop welcomed both locals and foreign tourists.

He worked at Lok Virsa for 27 years, becoming a regular feature at the annual Lok Mela. This year, however, high stall fees prevented him from participating.

“My hands tremble now. I get tired quickly. I had only a few pieces to exhibit, but could not afford the stall,” Riaz said with a sigh.

Despite health and financial challenges, he still receives orders enough to stay afloat, support his family, and even educate and marry off his children.

His son, Fayyaz Ahmad, has taken up the family craft, now creating wax portraits that appeal to a modern audience.

Peshawar, believed by many historians to mean “City of Artisans” or “Skilled People”, was once a cultural crossroads on the ancient Silk Road.

Its bazaars were famously named after trades coppersmiths’ Bazaar, Ironsmiths’ Bazaar, and even Storytellers’ Bazaar, Qissa Khwani. In such a city, craftsmanship was not a pastime but it was identity.

Wax painting, believed to have been brought from Kabul and refined under Mughal patronage, found a home here.

Its intricate technique uses linseed oil, powdered pigments, and limestone mixed with wax extracted from heated flax seeds a slow and meditative process that resists industrial replication.

But without government intervention and societal recognition, the craft now teeters on the brink.

For Riaz, the solution is simple ie education, exposure, and opportunity. He urges the government to reinitiate the Artisan Village program and establish platforms where craftspeople can showcase, sell, and teach their work.

“This art can’t be learned in a few days,” he insists. “It needs time, love, and patience. We need training centers, exhibitions, and most of all awareness.”

Though aging, Riaz is not bitter. “People only grow old when they stop working,” he smiles. “Everyone dies eventually, but those who quit their passion — they die every day.”

In a city that once celebrated its artisans, Riaz Ahmed remains a solitary torchbearer of a dwindling heritage. Whether his flame continues to burn depends not just on him but on those willing to value, protect, and invest in the culture he represents.

Recent Stories

SEC issues decision to create new units within Sharjah Police General Command

Dubai Chambers to host Dubai Business Forum – USA in New York this November

PTI seeks permission for August 5 Rally at Minar-e-Pakistan for Imran Khan’s r ..

Fourth edition of International Programme for Civil Aviation Leaders kicks off

Father, daughter swept away in flash floods after torrential rain in Rawalpindi

UAE Team Emirates-XRG's Isaac del Toro claims fifth win

Emirates Group launches massive talent drive to recruit over 17,000

Russian scientists develop first 3D-printed laryngeal implant to accelerate canc ..

UAE’s ‘Global Sustainable Aviation Marketplace’ institutionalised as ICAO ..

Major oil, gas deposit discovered off Polish Baltic coast

Fatima Bint Mubarak Ladies Sports Academy Launches nationwide sports festivals

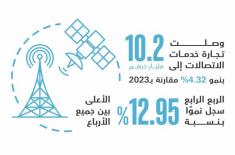

UAE telecom services trade up 4.3% to AED10.2 billion in 2024

More Stories From Pakistan

-

Peshawar’s wax art fading as patronage declines in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

9 minutes ago -

DC for ensuring sale of sugar at officially prescribed rates

9 minutes ago -

PM Shehbaz vows to transform National Police Academy into premier institution

9 minutes ago -

A man riding a motorcycle was hit by a passenger bus, three injured

9 minutes ago -

No vehicle plunging incident occurred in Rawalpindi: Distt Admin

9 minutes ago -

Akbar Peer Club clinches title in thrilling final of Aman Sports Gala volleyball tournament

9 minutes ago

-

Socks factory gutted

9 minutes ago -

Governor KP discusses security, political issues with Chairman Senate

9 minutes ago -

DPM Dar, Austria special envoy discuss education, tourism cooperation

19 minutes ago -

Dacoit arrested, illegal weapons recovered

19 minutes ago -

SU Announces LLB Examination Schedule

19 minutes ago -

AC seals petrol pump, Brick-kiln over violations

19 minutes ago