Unable To Get Medial Help, Kashmiri Dying As Lockdown Continues: Report

Mohammad Ali (@ChaudhryMAli88) Published October 07, 2019 | 10:59 PM

A leading American newspaper Monday carried heart-rending accounts of people dying because they could not get medical help in Indian Occupied Kashmir, which is under tight curfew since August 5 when New Delhi annexed the disputed state

"Two months after the Indian government revoked Kashmir's autonomy and imposed harsh security measures across the Kashmir Valley, doctors and patients here say the crackdown has taken many lives, in large part because of a government-imposed communication blackout, including shutting down the internet," The New York Times said in a dispatch from Heevan village.

Here is how the dispatch begins: "Saja Begum was cooking dinner when her son walked into the kitchen with a stricken look on his face. 'Mom,' he said. 'I have been bitten by a snake. I am going to die.' "Saja Begum could not call an ambulance: The Indian government had shut down Kashmir's cellular network. She then began a panicked, 16-hour odyssey to find an antidote that could save her 22-year-old son.

"While his leg began to swell and he grew faint, she trekked across a landscape of cutoff streets, security checkpoints, disconnected phones and hobbled doctors...

"For Saja Begum's family, time had become the enemy.

"On Aug. 13, her son, Amir Farooq Dar, a student whose college has been closed since early August, was tending his family's sheep in an orchard near the town of Baramulla when he was bitten by a krait, a poisonous snake.

"Most bites are fatal unless Polyvalent, an antivenin medication, is injected in the first six hours. Ms. Begum cinched a rope around his leg, hoping it would slow the poison. She then ran, with her son leaning against her, to the village public health center, which usually stocks the antidote. The center was closed.

"She shouted for help and begged for a ride to Baramulla's district hospital. But doctors there were unable to help, the family said, because they could not locate any antidote. They then arranged for an ambulance to take the young man to a hospital in Srinagar.

"Soldiers stopped the ambulance many times on the way, the family said. Mr. Dar was slowly closing his eyes. He told his mother, in a drowsy voice, that he could not feel his right leg.

"At least two hours had passed.

"After every failed trip, Saja Begum shouted at her husband, Farooq Ahmad Dar, 'Sell everything, but save him!' "Mr. Dar, 46, said he had never felt so helpless. 'I felt like pushing a knife into my chest,' he said.

"At 10:30 a.m. the next day, 16 hours after he was bitten, the younger Mr. Dar died. His parents then traveled 55 miles back home, in an ambulance, with his body.

"The antivenin arrived two days later at the hospital, from a city more than 150 miles away. It came in 30 vials in a van along with other medicines." The Times dispatch also highlighted the difficulties in obtaining medicines.

"Cancer patients who buy medicine online have been unable to place orders. Without cell service, doctors can't talk to each other, find specialists or get critical information to help them in life-or-death situations. And because most Kashmiris don't have landlines in their homes, they can't call for help." Sadaat, a doctor in a Kashmir hospital who did not want to be identified by his full name out of fear or reprisals, was quoted as saying, "At least a dozen patients have died because they could not call an ambulance or could not reach the hospital on time, the majority of them with heart-related disease.'' The report said many doctors interviewed by the Times said they could be fired for even speaking with reporters." It said, "Kashmiri doctors have also accused Indian security forces of directly harassing and intimidating medical personnel.

Indian officials claim, according to the report, claim that hospitals have been functioning normally, even under the restrictions, and that health care workers and emergency patients have been given passes to allow them to travel through checkpoints.

But several health officials, based on hospital records, estimated that hundreds of people have been left in an emergency situation without ambulances, and that many may have died as a result of that and other communication problems, though there are no centrally compiled figures, the Times said.

"People have died because they had no access to a phone or could not call an ambulance," Ramani Atkuri, one of more than a dozen Indian doctors who signed a recent letter urging the Indian government to lift the restrictions, said.

The Times said, "A new WhatsApp group called Save Heart Initiative that had helped in more than 13,000 cardiac emergencies and been celebrated in the Indian media as a Kashmiri success story has been rendered virtually defunct. Hundreds of Kashmiri doctors, and even some in the United States, were part of the group, uploading electrocardiograms and other vital information and then getting life-saving advice from one another.

"With no internet in the Kashmir Valley, doctors there can't use it." Doctors at Sri Maharaja Hari Singh Hospital in Srinagar, Kashmir's biggest city, told the Times there had been a 50 percent dip in the number of surgeries in the past two months because of the restrictions, as well as because of drug shortages.

Several young doctors said their work had been particularly hampered by the loss of mobile phone service. When they needed help from senior doctors, they lost precious time racing around the hospital searching for them.

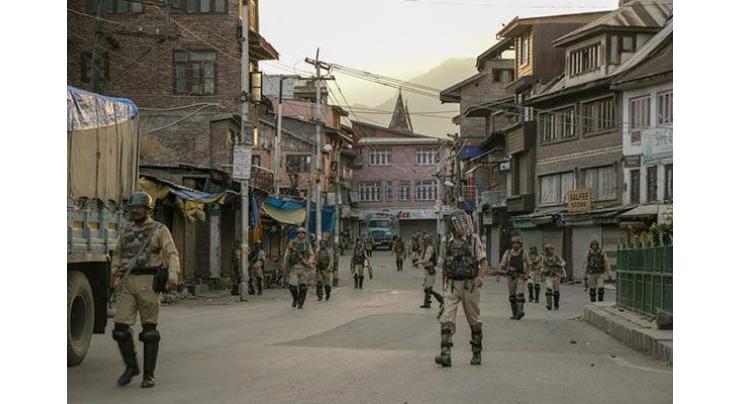

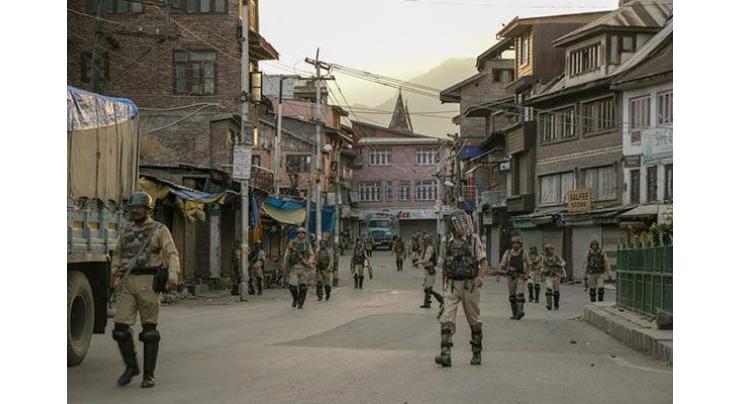

Hours before announcing the revocation of Kashmir's special status, Indian officials imposed a blanket of tough security measures, cutting off the internet and phone services and jailing thousands of Kashmiri political leaders, academics and activists. It also imposed a strict curfew, limiting movement in the Kashmir Valley, home to approximately eight million people.

Kashmir has been racked by a separatist conflict for years, and Indian officials, including Prime Minister Narendra Modi, have claimed the new arrangement will bring peace.

But several Kashmiri doctors said dozens of preventable deaths might have happened because of the blockade, according to the dispatch, which also said: In late August, a Kashmiri doctor, Omar Salim, a urologist, rode a bicycle on a deserted street to Srinagar's hub of media offices, in a doctor's apron, a poster hung to his chest. His plea: restore phone and internet service.

He was promptly arrested. Police officers let him go after a few hours with a warning not to do it again." "We may not be in a formal prison, but this is nothing less than incarceration," Dr. Salim said in a recent interview.

A cardiologist who works at a Srinagar hospital said he had recently received a patient who had suffered a heart attack. The patient needed a procedure that required the help of a specialized technician, but the technician was not at the hospital.

Fearing that the patient could die, and with no way to call the technician, the cardiologist drove five miles in pitch darkness to the technician's neighbourhood and searched for him. The doctor didn't know exactly where he lived and had to keep asking people to lead him to the technician's house.

The doctor said that he and the technician managed to save the patient's life, but that Kashmir has been 'thrown into the Stone Age.' Several Kashmiri doctors said pediatric care and maternity services were among the hardest hit.

The dispatch said, "Last month, Raziya Khan was pregnant when she developed complications. But she and her husband, Bilal Mandoo, who are poor Apple farmers, live in a small village seven miles from the nearest hospital and couldn't call an ambulance because of the phone blockages.

The couple walked the seven miles, taking hours because of her worsening condition. They made it to the hospital, but were then sent to a bigger hospital in Srinagar. It was too late, and they lost their baby." "Had there been a phone working, I would have called an ambulance right to my house," Mandoo was quoted as saying.

Related Topics

Recent Stories

Today Gold Rate in Pakistan 26 April 2024

ICC Womens T20 World Cup Qualifier, Match 2: Ireland Women open with Comfortable ..

Robinson, bowlers help New Zealand go 2-1 up against Pakistan

Shahzeb Chachar to hold khuli kachehri on April 26

Heatwave amid Israel's aggression in Gaza brings new misery, disease risk

Tourism must change, mayor says as Venice launches entry fee

Court adjourns Judicial Complex attack case till May 17

Nasreen Noori’s book ‘Popatan Jahra Khwab’ launched

Wafaqi Mohtasib inspection team visits Excise and taxation office

AJLAC announces 5th Conference titled ‘People’s Mandate: Safeguarding Civil ..

Pak-US officials engage to enhance trade, investment ties

IBCC to promote educational excellence, expand regional presence

More Stories From Kashmir

-

Azad Jammu Kashmir Prime Minister Chaudhry Anwar ul Haq condoles over the demise of an ex-AJK Minist ..

11 hours ago -

AJK observes World Earth Day with a call to action on plastic pollution

3 days ago -

AJK PM Marks One Year in Office, Vows to Continue Serving with Zeal

5 days ago -

Mehbooba Mufti vows to fight India's hostile policy

5 days ago -

Azad Jammu Kashmir Prime Minister Chaudhry Anwar ul Haq Pays visit to special Advisor's residence

5 days ago -

Mirpur Police arrest 68 suspects of food outlet attack

6 days ago

-

Modi govt broken all records of oppression to win elections: President AJK

7 days ago -

AJK business forum proposes measures for industrial growth

7 days ago -

MoU signed for skilled manpower in AJK: PM lauds initiative

8 days ago -

Fresh wave of freedom struggle gains momentum in IIOJK

8 days ago -

JKNF clarifies Muneer Khan's political shift

8 days ago -

AJK gov’t initiates efforts to revive sick industrial units

8 days ago